Or, "How I got my slanted eyes."

Victoriano Joanino y Caboral

HOW IT ALL STARTED

As a child, I became aware of the lack of male figures in my family. I had a Chamorro grandmother, but never a word about her husband. I heard about Mamá, my great grandmother, as she was called in the Spanish style of those days. But I never heard of a Papá.

By the time I was a teenager, I had put the pieces of the puzzle together somewhat.

Mamá had never married. But, she had six children, each with a different father, although it is debatable if two of the six shared the same father.

The story was that Mamá was an only child. This we can verify, since we have the 1897 Census and there it is. Pedro Torres y Rodríguez is married to Josefa Pérez y San Nicolás and they have but one child, a daughter, Maria Torres y Pérez, or Mamá.

As Mamá was an only child, her parents never allowed her to get married. For her to get married meant to leave mom and dad and be absorbed into the husband's family. Who would care for Pedro and Josefa in their old age?

Still, human nature being what it is, Mamá had six children. The oldest of the six was my grandmother María, who became the pillar and rock foundation for the small clan of six children and Mamá, nicknamed the familian Kitå'an, after Mamá, whose name María was affectionately changed to Mariquita, and Kita for short. Kita's children were the Kitå'an.

GRANDMA'S DAD

I never knew Mamá, but I knew her daughter, my grandmother María. I was 18 when she passed away. A few years after my grandmother died, I started to pester her cousin, my grand aunt Carmen Pérez Cruz (married Guzmán), who knew all the family secrets.

One day she let me know. She said my great grandfather was a Filipino. "

Eskribienten i Gobietno," she said. "Clerk of the Governor."

But what was his name?

All she could remember was something that sounded like HUA - NINO.

I was bewildered. Was that his first name? Juanino? Like Juanito?

Or was it his last name?

Or was it both names? Juan Nino? Juan Ino?

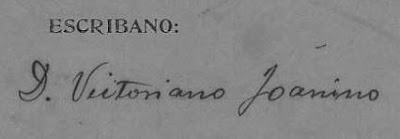

THEN I FOUND THIS

This is the signature of the land clerk on a land document, signed in Agaña, Guam in 1900. My grandmother was born in 1899.

The signature clearly says "Victoriano Joanino C."

In Spanish, the father's surname comes first. Then comes the materal name, which can be abbreviated, as it is here, as a C.

Using the American style, this man would have been Victoriano C. Joanino. Joanino! I found my great grandfather's name and signature!

THE MANILA PHONE BOOK

Years passed and by the early 1990s, I went to Manila as a young priest buying things for my parish. While there, I decided to look up Joanino in the Manila phone book. All I can say is thanks be to God my great grandfather's name was not Cruz or Reyes or Santos. I'd still be in Manila today looking for my great grandfather if his name was one of those.

Instead, I found just six Joaninos in the phone book. Easy! I dialled the first one. "Hello, my name is Father Eric Forbes, a priest from Guam. I am looking for my relatives. Children of Victoriano Joanino."

The first Joanino house did not know of any Victoriano. Nor did the second. The third house may not have even answered. I don't remember!

But the third or fourth house did! The woman who answered the phone responded excitedly. "That is my Lolo! (Grandpa)"

Her name was Thelma and she said the family lived in the province of Nueva Ecija, though some of the family lived in Manila. At that very moment, she said, her dad was visiting her home in Manila. I went to see him a day or two later. I almost died. He was skin and bones, just like my grandmother, who would have been his half-sister.

This man confirmed that his father Victoriano had been exiled to Guam. "With Mabini," they said, but that wasn't true, as I was to find out later. But this is what families do. They add spice to the family legends, just like fishermen add pounds and inches to the fish they claim to catch!

WHO WAS VICTORIANO?

Gramps in his younger days.

Victoriano was a rebel. A member of the Katipunan, or nationalist Filipinos fighting Spain. But he was an educated rebel; one who could understand, speak and write in Spanish.

He was originally from Tayug, Pangasinan. He was of Ilocano descent, his parents having moved to Pangasinan from Cava, La Union. The family confirmed that his maternal name was Caboral; the "C" in the Guam land document. We don't know where he got his education or how far he went in school, but the Joaninos in Tayug were part of the educated middle class that supplied minor civic servants.

Relatives in the Philippines told me the original name was Suanino and it was Chinese. In time it became Joanino; easier for the Spaniards to say, I suppose.

In the fall of 1896, the Philippine Revolution broke out. The Spaniards started to arrest numerous rebel leaders, big shots and less important ones, like Victoriano.

In Tayug, besides Victoriano, a certain Teodórico Vidal was also arrested. From then on, for some years, Victoriano and Teodórico shared the same fate; arrested at the same time, convicted at the same time and sentenced at the same time. Victoriano's court case files are missing, but Teodórico's are not. In his files, he is described as a Mason and an enemy of Spain. We can be sure Victoriano was charged with the same accusations.

In December of 1896, after having spent some time in the Bilibid prison, my great grandfather was deported, with his Tayug townmate Teodórico, to Guam. They arrived on Guam in February of 1897.

The Spanish Government document showing his arrival on Guam in 1897

LIFE ON GUAM

As one can see from the land record above, Victoriano did not spend his life behind bars on Guam as a political prisoner. He was put to work as a government clerk, since he was educated enough to do that.

When the Americans came in 1899, he continued in this post. While still on Guam, Mabini and the other famous nationalist leaders against the Americans were deported to Guam in 1901. That's why Victoriano or his family claimed he was "with Mabini on Guam," but under different circumstances.

Besides all this, Victoriano fathered my grandmother María, born in 1899.

Victoriano Joanino named "escribano" or "scribe/clerk" in a court proceeding on Guam in 1901. The court record was still written in Spanish at the time.

BACK TO THE PHILIPPINES, BUT...

Sometime in 1901 or 1902, he was free to return to the Philippines. When he returned to Tayug, he found out that his wife had re-married, thinking that he had died.

Disgusted with this, Victoriano moved not far from Tayug, but in the neighboring province of Nueva Ecija, to a town called Lupao where he found a second wife and raised a family. It wasn't a real town yet, and Victoriano was one of the civic leaders who lead the effort to elevate the community. In 1913, Lupao became an official town and Victoriano was credited with making that happen. He became the town's first Mayor (or President). To this day, the Joaninos are a well-known and politically active family in Lupao.

THE IRONY OF IT ALL

My great grandfather was a Mason and, in time, an Aglipayan, a church which broke off from the Roman Catholic Church to become an independent, "Filipino Catholic Church."

I wonder how he would feel knowing his great grandson is not only a Catholic priest, but also a friar - like the ones he fought against, believing that the friars were the villains responsible for the oppression of the Filipino people!

My grandmother, daughter of Victoriano